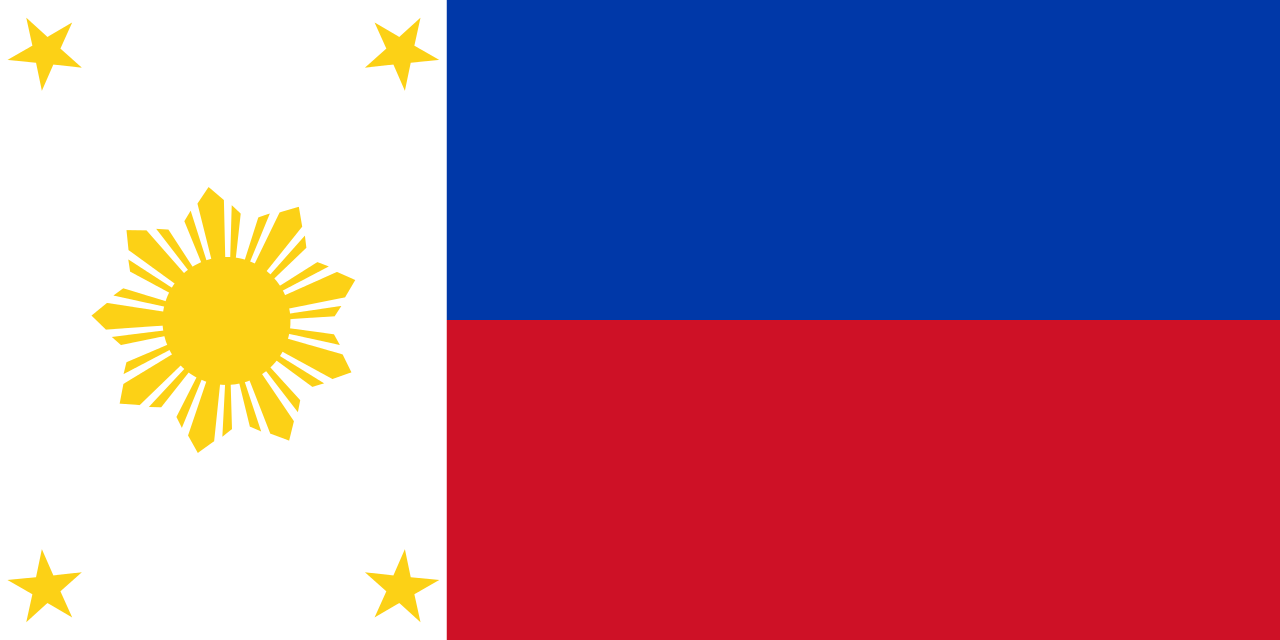

On July 3, 1946, the day before the territory of the Philippines declared independence from the United States, President Truman recorded a message to the people of the Philippines.

“To the People of the Philippines,” he began, “I am indeed happy to be able to join with you in the formal inauguration of the Republic of the Philippines.”

The United States and the Philippines were at war for three years after Spain ceded the Philippines (as well as Puerto Rico and Guam) to the United States. The U.S. officially agreed that the Philippines could become independent in 1934, with a ten year transition plan which was lengthened by the Second World War.

“This is a proud day for our two countries,” Truman continued. “For the Philippines it marks the end of a centuries-old struggle for freedom. For the United States it marks the end of a period of almost fifty years of cooperation with the Philippines looking toward independence.”

The Philippines always wanted independence

While the people of the Philippines did not have complete consensus on independence, and there was a statehood movement there as well as people in the states who wanted the Philippines to become a state, the Philippines was destined for independence from the beginning of their relationship with the United States.

Emilio Aguinaldo proclaimed a Declaration of Independence for the Philippines in 1898, and the war between the U.S. and the Philippines ended in 1902 with an organic act and general amnesty for everyone who had taken part in the war. In 1916, the Jones Law, or Philippine Autonomy Act, stated that the Philippines would be independent: “It is, as it has always been, the purpose of the people of the United States to withdraw their sovereignty over Philippine Islands and to recognize their independence as soon as a stable government can be established therein.”

President Truman’s message acknowledged that independence could be difficult. “But the United States has faith in the ability and in the determination of the Philippine people to solve the problems confronting their country,” he said. “The men who defied Magellan, who fought for a Republic in 1898, and who more recently on Bataan, Corregidor, and at a hundred other unsung battlegrounds in the Philippines flung back the Japanese challenge, will not lack the courage which is necessary to make government work in peace as well as in war. The will to succeed, I am sure, will continue to govern the actions of the Philippine people.”

The relationship going forward

Truman also spoke about the plans for the future between the United States and the Philippines. “The United States, moreover, will continue to assist the Philippines in every way possible,” he said. “A formal compact is being dissolved. The compact of faith and understanding between the two peoples can never be dissolved… We of the United States feel that we are merely entering into a new partnership with the Philippines–a partnership of two free and sovereign nations working in harmony and understanding.”

Of course, this was intended to be a positive and inspiring message. There were issues after that statement. Only about 10% of the U.S. nationals from the Philippines took up an offer on the part of the federal government to send them back to the Philippines. Those who stayed in the states lost their status as U.S. nationals and had to go through the lengthy process of naturalization as citizens if they wanted to stay.

Veterans from the Philippines lost their benefits, which they had expected to keep. Some of the aid they anticipated from the United States ended up being loans, which were hard on their economy. The Japanese occupation during World War II had ongoing political consequences; since the Philippines continued to be economically dependent on the United States, the U.S. had quite a bit of influence in the new nation. A treaty between the new republic and the U.S. in 1947 settled some trade and military questions which had lingered after independence, but it contained some controversial elements.

Lessons for Puerto Rico

Truman’s remarks ended with, “May God protect and preserve the Republic of the Philippines!” The statement presented independence as a culmination of the planned relationship between the Philippines and the United States.

Puerto Rico has never been slated for independence, as the Philippines was. Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens, as the residents of the Philippines never were, and statehood has frequently been named as the goal for Puerto Rico, from the earliest days of the relationship. U.S. statehood is the political status most similar to the home rule the autonomists wanted from Spain before the Spanish-American War.

But Puerto Rico can look at the experience of the Philippines to get an idea of how independence from the United States might work. It was a friendly dissolution, but it was certainly a separation. The Philippines did not keep the advantages of being a U.S. territory. They did not have the chance to continue as U.S. nationals. They did not succeed in negotiating free trade or free passage.

There is no reason to think that the Philippines regretted their choice of independence. Puerto Rico could be equally successful. The biggest difference is that Puerto Rico voters have never chosen independence in any status vote. They have never elected any member of the Independence Party as Governor or Resident Commissioner of Puerto Rico. At this point, the specter of independence is just a straw man to delay statehood. Voters should look to history before being distracted by it.

No responses yet