President Trump is not the only federal leader who has a Twitter account and knows how to use it.

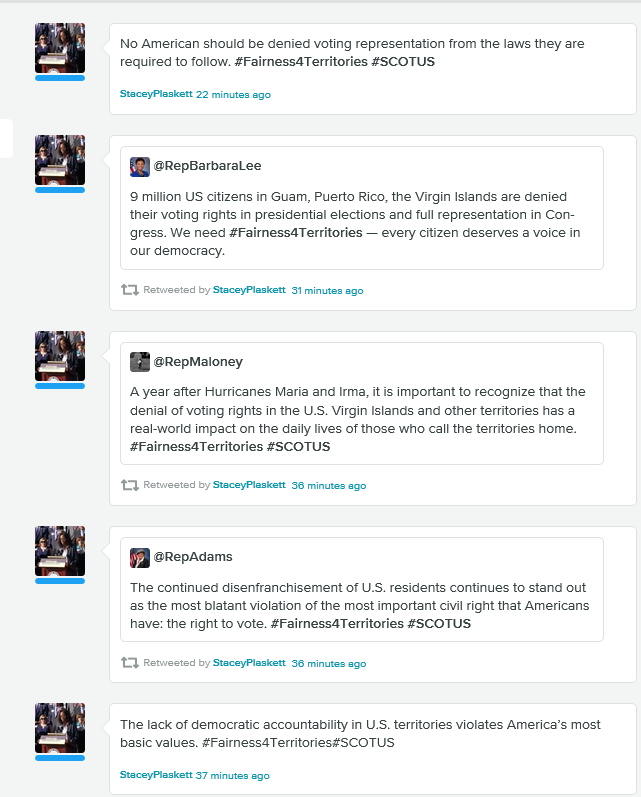

The non-voting Congresswoman from U.S. Virgin Islands recently was joined by a handful of colleagues in the U.S. House of Representatives in launching a Twitter campaign expressing exasperation with the anomalies of federal territorial law and policy. This barrage of Congressional e-mails was apparently orchestrated on the same day as court and diplomatic proceedings on territorial political status issues.

If that is so there is a possibility that the Congressional tweets were suggested by Neal Weare, a lobbyist fundraiser whose non-profit organization has brought cases in the federal court seeking extension of constitutional rights in the states of the union to the U.S. territories.

In particular, Congresswoman Plaskett and other members including Rep. Carolyn Maloney and Rep. Barbara Lee decried the state of limbo in which the Congress and federal courts have left US citizens in American territories classified as “unincorporated,” and consequently denied rights of citizenship equal to Americans in incorporated territories and the 50 states.

As originally invented by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1901, non-incorporation was a temporary interim status until Congress made a decision either granting citizenship and integration (e.g. Hawaii), or denying citizenship and eventually recognizing separate nationhood for the territory (e.g. Philippines).

Then in 1922 an errant but never challenged or reversed high court ruling continued non-incorporated status for Puerto Rico after Congress granted U.S. citizenship. That deviation from court precedent and anti-colonial territorial status tradition (going back to the Northwest Ordinance written by Thomas Jefferson) was then expanded to create political status purgatory for the U.S. Virgin Islands and three other small off shore possessions.

Plaskett’s tweets together with its companion messages offer no solutions. However, in failing to do so these messages reveal that the unincorporated territory concept has outlived its relevance as a metaphor for a transitional status never intended to be permanent.

In a sense those in territories like Guam, U.S. Virgin Islands and other small island possessions who are taking Neal Weare’s advice are in turn making demands for state-like rights that can lead only to incorporation, but without the promise of eventual statehood.

Instead of integration into an existing state, or, in the case of Puerto Rico admission as a state, the controversial lobbyist is trolling for donations to his non-profit advocating special rights and privileges to make limited civil rights of U.S. citizens in territories more tolerable.

It is reported that Weare is proposing to make unincorporated status more beneficial by securing federal voting rights without federal taxes. So I guess you’d call that representation without taxation.

Weare doesn’t care if his ideas are dead on arrival. He just cashes in on the desperation of his donors, while he laughs all the way to the bank.

Under the U.S. Constitution there is no right of representation without statehood, and there likely is no statehood for small territories except by integration into an existing state. There sure as heck will be no voting rights without statehood, because that is unconstitutional. Only states have federal voting rights, not territories.

But it is wrong to assume as many Weare followers do that the alternative to incorporation as a promise of statehood is a non-territorial status called “commonwealth” that could combine features of statehood and nationhood. If defined by Congress in a federal statute “commonwealth” is territorial status by another name.

It is next suggested by Weare’s donors that a constitutional amendment could create some status different than territory, but not a state or nation. Of course, a constitutional amendment can create a new political status, but is not relevant until it happens, because it would not be within the current constitutional rules of political status.

Under the current U.S. Constitution the status choices are territory, state and nation. Territories can be called commonwealth or incorporated or unincorporated, but those names are statutory not constitutional, and do not change the status from territory to anything else.

Incorporation and non-incorporation, like commonwealth, have whatever meaning Congress and courts may determine in the exercise of respective powers over territories. Incorporation is rescindable whether anyone cares to admit it or not. An incorporated territory like a so-called unincorporated territory can be declared a nation, a state, or a commonwealth but until then remains a territory.

A nation can be called independent or a free associated state if so denominated by treaty. But with or without a free association treaty, a nation is no longer a territory and is not a state, but could be a territory or a state if Congress agreed.

What does seem to be true here is that applying the 14th Amendment to a territory as Weare seeks would be in effect permanent incorporation. But if done without a commitment leading to statehood it would not confer voting rights of states and therefore would be an even more colonial status than non-incorporation.

All that said, the real truism illustrated here is that incorporation is not a status so much as a statutory declaration that a territory has been joined into the union, and the U.S. Constitution applies to the extent consistent with territorial status but not statehood. Non-incorporation is a declaration of US sovereign rule and U.S. nationality of the territorial population.

But that is not permanent until admission as a state. So non-voting representative Plaskett and her colleagues may have unintentionally forced all advocates of democratization for all the territories to realize the use of the terms “incorporated” and “unincorporated” no longer define the status options or issues that Congress needs to address.

Instead of defining the territories in those anachronistic terms, the current territories should be defined simply as U.S. territories with distinct political cultures, and populations with statutory U.S. nationality. The U.S. nationals in these federal territorial reservations with local self-government organized under federal law are classified as provisional U.S. citizens under federal territorial statutes in the case of Puerto Rico, Guam, U.S. Virgin Islands and Northern Mariana Islands.

As such, these territories have a right to informed self-determination between integration into the federal model of statehood with equal citizenship rights, or nationhood with equal citizenship rights (with or without a treaty of free association), or to continued territorial status with local self-government but not full democracy at the national level unless the U.S. Constitution is amended to provide otherwise.

Territorial status will persist until permanent status is chosen on terms acceptable to Congress and the people concerned.

No responses yet